With each male specimen who steps into the passenger seat of her little overheated car, Faber adds another piece to the puzzle of this alien kerb-crawler. What she does with the hitchhikers picked up in lonely glens we learn only slowly, by which time our fascination with Isserley and her own victimhood easily eclipses the gruesome fate that awaits them. Driving all day at funereal pace along the empty roads of northern Scotland, she is after one thing: well-muscled men.

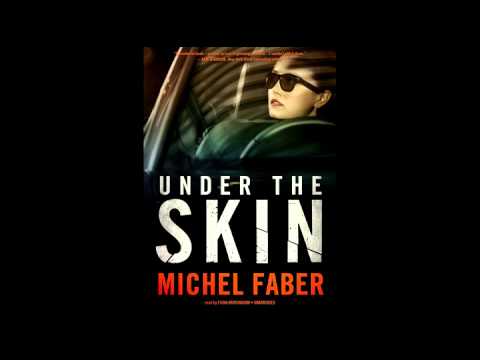

Like her creator, we are never quite sure where his Isserley, a small, bespectacled being with a perfect nose and curiously buoyant breasts, comes from.

So when Faber finally sat down to write a novel, it is not surprising that he adopted the guise of someone not of this world, nor even of this galaxy. Was Faber really who he said he was, you wondered, or was he the Dr Jekyll to Irvine Welsh’s Mr Hyde, or some sleeker incarnation of Alasdair Gray? Here was a ventriloquist with a whole Babel of voices to throw: artists making nothing out of something, cosmetic surgery junkies obsessed with the unseen and dead people coolly assessing their killers. You don’t often see satire stirred with so humane a hand, or tragedy handled with so light a touch. This air of mystery thickened with the tantalising glimpses of something big beneath the bushel in such perfectly turned stories as “Sheep”, “The Red Cement Truck” and “The Perfect W”. On the jacket of his one collection of short stories, Some Rain Must Fall, we were asked to believe that he was a Dutch pickle-packer who studied Anglo-Saxon in Australia before giving it all up to become a cleaner somewhere near Inverness.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)